-

Search -

Accessibility -

Members Login

“As local as possible, as international as necessary”

Note: You can read this report in your preferred language using the Google Translate tool at the bottom of the page. The paper is also available to download in English here.

Quick links:

The global humanitarian system is at a breaking point. Needs are rising, yet funding has collapsed at unprecedented scale. In 2025, almost 200 million people identified as needing assistance will not be targeted by humanitarian response plans. As per OCHA’s Financial Tracking Services (FTS) at the start of Quarter 4, 2025, total humanitarian funding stood at USD 18.30 billion – surpassing even the most pessimistic forecasts. Frontline staff are being forced into deciding who lives and who dies.

Past and present reform efforts such as the Grand Bargain have delivered or proposed efficiencies, but left the traditional humanitarian paradigm largely intact: large-scale internationally led responses coordinated and operationalised primarily through UN agencies. Likewise, the current reform agenda of the Humanitarian Reset presents a formal humanitarian system that will be smaller, operating in fewer places, but otherwise looks much the same. Efficiency gains have not translated into more funding. Instead, the system remains over-reliant on few donors, trapped in competition, and resistant to ceding power or presence. Business as usual, however, is no longer acceptable or viable.

This paper argues a fundamental shift is needed: from competition to collaboration, from international leadership to local leadership with international support, and from project delivery to people-centred outcomes.

This paper proposes humanitarian complementarity as the organising framework for a more effective, equitable, and sustainable system. It focuses primarily on NGO inter-complementarity and UN/NGO complementarity, not necessarily looking to establish an overall blueprint for the system. The ideas presented are to provoke discussion. The preliminary recommendations will be further elaborated in a forthcoming series of ICVA roundtables.

Complementarity is the deliberate and equitable collaboration between diverse actors to ensure assistance and protection are provided by those who are best placed in each context. It is grounded in humanitarian principles, rooted in community needs, and operationalised through shared power, resources, and decision-making.

Humanitarian complementarity goes beyond traditional localisation objectives. It is a cultural shift founded on each actor contributing their unique value-add in support of short- and long-term interests of affected communities. Achieving complementarity in humanitarian contexts, requires a concerted effort to address a number of systemic barriers, including:

Only by working together—each actor focused on its unique value and accountable to the people we serve—can we build a humanitarian system that is people-centred, sustainable, and fit for the future.

This paper proposes the following preliminary recommendations, which will be further developed in a series of ICVA roundtables:

To further forge their leadership role in humanitarian response mechanisms, L/NNGOs are encouraged to:

Beyond current reform efforts, including UN80, UN agencies are encouraged to:

In the spirit of “as international as necessary, as local as possible” INGOs are encouraged to:

Understanding and working within the range of their diversity, donors are encouraged to:

Humanitarian crises are growing in number, duration, and complexity: Conflicts are more protracted, climate-related disasters are more frequent, and political instability is increasing. In 2025, almost 200 million people identified as needing humanitarian assistance have been removed from response plans– with little to no alternative safety nets. The system is being forced to triage at unprecedented levels.

On the ground, frontline staff are being asked to make impossible decisions, literally determining who receives life-saving support and who does not. The moral, operational and financial pressure on humanitarian actors has never been greater.

While grappling with ever-increasing needs and complexity,the global humanitarian system continues to experience an unprecedented financing shortfall: At the start of Quarter 4, 2025, total funding levels standing at US $18 billion, surpassing even the most pessimistic funding scenarios. The funding cuts, including that of the United States and several European donors, have exposed the fragility of a system over-reliant on a handful of core donors and the prioritised Global Humanitarian Response Plan has just 23% of funding needs met. Exacerbating the fall in humanitarian funding are similar cuts affecting development, peace, human rights, health, and climate activities. On the other hand, military spending increased by $1.5 trillion in 2024.

The prevailing humanitarian model was built on a paradigm of international strength. Responses are largely organised through funding appeals, project proposals, and centralised coordination structures. Large agencies compete for funding, visibility, and operational footprint. Community needs are seen through a lens of institutional mandates and fundraising efforts. Pivoting towards “as local as possible” has proven challenging, to say the least. However, with resources shrinking, and needs rising, business as usual is no longer acceptable – or even possible.

Founded on a people-centred approach, the system must find viable means to identify and support the best placed actor to work with and for communities. Agencies who are not indispensable must step aside, even if this signifies a cut in funding and/or reduction of operational footprint.

Among actors present, true and equitable partnerships must be built between NGOs, local and national authorities, self-help groups and mutual aid groups (MAG), the private sector, UN agencies, and funders. Only by working together and sharing services will the sector be able to maximise efficiencies and begin to address the apparent declining commitment to solidarity.

This paper, was developed by ICVA in consultation with its Board and members of the Humanitarian Finance Working Group, with special thanks to NRC for developing a first draft and CARE, Oxfam and DRC. It makes the case for the necessity of a humanitarian system rooted in complementarity: each actor playing its part, centred on community-led response, setting aside competition and institutional self-interest.

The paper argues that realising complementarity will require a genuine cultural shift, driving changes in incentive structures and ways of working. It illustrates this with a deep dive into complementarity among and between the diversity of NGOs and the support required from donors and UN agencies. While it does not attempt to address the complementarity among all actors, including the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (RC/RC Movement), it is hoped that it contributes to advancing the needed reform efforts.

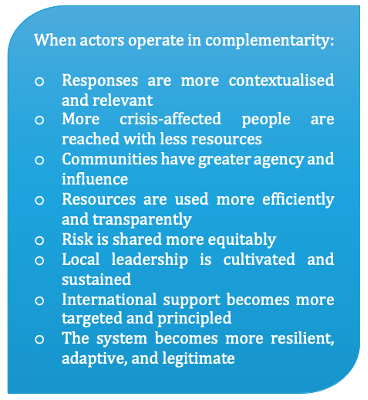

Humanitarian complementarity is both a process and an outcome where capacities – local, national, regional, international – are harnessed and combined to support the best possible humanitarian outcomes. Complementarity must be rooted in a people-centred approach, where communities’ needs, priorities, and capacities drive response decisions and implementation. It shifts the focus from “who leads” to “what is needed and who is best placed to deliver it.”

Complementarity is not about cutting costs. Building equitable partnerships – covering full costs, providing technical support, and supporting multiple smaller actors – may require greater investment in the short term. Complementarity does however enable more relevant, timely, and sustainable responses by ensuring that those closest to communities lead where they are best placed. It strengthens local systems, reduces duplication, improves accountability, and builds long-term capacity, ultimately allowing the system to reach people more effectively and reduce the need for repeated cycles of international aid.

Complementarity is not a new idea – it is the extension of the principles of partnership, and underlines much of the reform efforts of the Grand Bargain. It reflects the reality of a diverse humanitarian ecosystem, where each actor brings unique mandates, experience, and value.

At the heart of complementarity is the principle of the best-placed actor: the organisation or institution with the most appropriate access, legitimacy, capacity, and contextual understanding to meet a particular need in a specific context.

The best-placed actor should ultimately be defined by affected people themselves. It therefore depends in large part on effective coordination mechanisms. It should also by default accept the transient nature of international assistance, and the continual need to support national response and protection systems, including governments and civil society actors.

Complementarity builds on – but goes beyond – localisation and the nexus:

In short, localisation is about who leads, the nexus is about what is connected. Complementarity is about how we work together to achieve all this in practice.

Realising complementarity requires a series of structural and operational shifts which promote collaboration over competition, inclusion over exclusion, and facilitation over doing. These mindset and design shifts include moving:

| From… | To… | |

| A focus on compliance and project delivery | ➡️ | Consistently ensuring affected people’s needs are met in line with their priorities including through empowered community change agents and local actors. |

| Individualistic and protectionist mindsets of “my agency is best placed and can add the most value” | ➡️ | Identifying “How can we ensure value is added?” |

| Agency-focused technical teams | ➡️ | Shared services which provide back-office support for the multiplicity of actors including L/NNGOs, INGOs, and UN actors, as needed. |

| Project subcontracting | ➡️ | Co-creation and shared leadership. |

| Competition for visibility and resources | ➡️ | Collective action for outcomes. |

| Exclusion through language, bureaucracy, and compliance requirements | ➡️ | Facilitated inclusion of staff and partners with limited English or literacy. |

| Incentives and performance metrics that reward international operational footprint | ➡️ | Rewarding collaboration and effective exit strategies. |

| Donor/funder-oriented partnerships and budget allocations | ➡️ | Equitable partnerships and full cost coverage. |

Each crisis and community is unique, as is the support required by domestic resources and institutions. Complementarity may not imply reducing the role of international actors in critical contexts, but it may require redefining roles.

The adaptation needed to achieve the best possible humanitarian outcomes will depend on multiple factors including the nature of the crisis – disaster or conflict, sudden-onset or protracted, and national capacities/engagement. For example, a sudden-onset, non-conflict-related crisis, may require donors or intermediaries making funds available to local actors and/or shared services to support security, data insights, and access negotiations. While a complex crisis, where response is required in areas controlled by de facto authorities, may require international actors working across frontlines and providing protection by presence.

Governments and local/national civil society capacity/access also varies dramatically. While in some cases state systems may be absent or collapsed, in others, governments may be strong partners in disaster response. Governments may also be parties to conflict, restrict access, or exclude marginalised groups. Likewise, as per the large number of civil society mappings conducted in humanitarian contexts, the strength, presence, and capacity-building needs of the diversity of local and national civil society actors varies considerably across humanitarian contexts. Each context therefore necessitates nuanced consideration.

Humanitarian complementarity recognises that no single actor can meet the full range of humanitarian needs. The strength of the system lies in its diversity. However, this diversity is too often poorly leveraged.

It is essential to acknowledge at the outset that it is difficult to speak in generalities. UN agencies and NGOs vary widely in mandate, size, funding sources, staffing, governance, and ways of working. Furthermore, there is also a tendency for these actors to overlap, playing the roles of one another, as needed in each context.

The following section therefore attempts to draw out patterns and tendencies that can help contribute to further reflections.

NGOs as a collective have saved and protected millions of lives and livelihoods. At their best, NGOs embody civic engagement and solidarity with affected people. Many operate with decentralised structures and comparatively lower operating costs to UN or private sector actors. Their flexibility and community trust often makes them the first to identify and respond to emerging needs.

Across contexts, NGOs are generally direct service providers of life-saving assistance, essential services, and protection from violence at the community level. They ensure local voices are heard and needs are met, advocate for the rights and protection of affected people, play a critical role in innovation and knowledge transfer, and support local systems including markets and the private sector.

As per the principles of “as local as possible, as international as necessary”, leveraging the value-add among local and national NGOs and international NGOs is critical to meet humanitarian objectives.

| Examples of NGO innovation that transformed lives, livelihoods, and the sector |

|---|

| The following models – developed in partnership with communities – have reduced morbidity, mortality, and costs. They have been adopted and scaled up globally by governments, NGOs, & the UN: The Community Health Worker model pioneered by BRAC in Bangladesh has contributed to significant increases in antenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and declines in neonatal mortality. Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) and CMAM Surge, pioneered by Valid International & Concern Worldwide, achieves significantly higher recovery rates, lower mortality and costs, and is the standard of care for Severe Acute Malnutrition. Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction including participatory risk mapping, early warning, and evacuation-planning with barangay communities was pioneered by the Citizens’ Disaster Response Centre (CDRC) and Filipino NGOs. It informed the Hyogo and Sendai Frameworks and has been widely adopted. The Emergency Medical Response model with Rapid Deployment Medical Teams, Mobile Hospitals, and Standardised Kits was pioneered by MSF and has become the global template. The Sphere Standards, led by NGOs, changed the humanitarian sector by creating a shared framework and technical clarity on minimum acceptable standards in emergency response. The Village Savings & Loan Associations model, pioneered by CARE, harnessed local practices of group savings, which has sustainably and financially empowered millions of women, refugees, and other crisis-affected populations. For more examples of NGO-led social innovation see Bond’s Social Innovation review. |

Local and national non-governmental organisations (L/NNGOs) are the most diverse actors in the system. Their size can range from small volunteer-based community groups to multi-million budget institutions. They may work independently or be members of global networks, such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. They include women-led and women rights organisations, refugee- and youth-led organisations, organisations representing persons with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ organisations. All are critical components of the social safety nets required in any community. Along with other local actors (e.g. local and national governments, faith leaders, community groups, the local private sector), they are present before, during, and after crises, and are held primarily accountable by communities for meeting their needs.

L/NNGOs actors will typically bring to a response the following value proposition:

Like L/NNGOs, international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) are also highly diverse. They include large, federated organisations, specialised technical agencies, and organisations ranging from multi-mandated development/humanitarian and peace-building ones to purely humanitarian operational agencies. INGOs may operate exclusively through partnership models, work directly or through a mix of modalities. Key elements of their value-add typically include:

The support of the UN community is an important enabler of many NGOs’ operations. UN agencies are at the heart of the multilateral system, put in place by States to promote and protect their common interests. The critical functions of the UN, include:

As HPG’s 2019 research showed, the humanitarian system is not designed to naturally evolve toward complementarity: decision-making remains centralised, incentives favour institutional control, and local capacities are often undervalued. ICVA consultations with NGOs in 2025 echo these 2019 findings – despite years of discussion and advocacy, many of the same structural and cultural barriers persist, and in some cases have deepened with the current funding crisis.

These barriers – cultural, structural, financial, and political – are deeply embedded in how the humanitarian system operates. Addressing them requires collective leadership and a fundamental reorientation of incentives.

The humanitarian system arguably operates as a competitive aid economy. Success is largely measured by institutional prestige, budget size, and operational footprint, rather than collaboration, partnership equity, or outcomes for affected people. In general, staff are incentivised to protect organisational interests, retain control, and compete for resources, rather than to build trust, share leadership, or step aside when others are better placed to deliver.

Even where individuals support complementarity, institutional systems and incentive structures make it difficult to operationalise in practice. Without changes to how performance is measured and rewarded, complementarity will remain secondary to institutional imperatives.

The emphasis on performance metrics such as footprint and funding growth must be adjusted, and, instead, community- and partnership-focused metrics should be prioritised. These could include, for example: proportion of communities reporting that their needs are met in line with priorities, activities handed over, or local organisations successfully supported to access international funding. The system must measure what counts, rather than what can be easily counted.

Many L/NNGOs report being perceived as less “principled” than international actors – a perception that is not supported by evidence. In reality, upholding humanitarian principles is a challenge for all actors – UN agencies, INGOs, and L/NNGOs alike – especially given complex national and international regulatory environments, including bureaucratic and administrative impediments, constraints related to counter-terrorism, sanctions, and banking regulations.

L/NNGOs can face higher levels of physical and political risks, harassment, and/or defunding. UN integration models – combining humanitarian, political, and peacekeeping mandates – can constrain protection advocacy and principled negotiations.

Rather than question who is “more principled,” humanitarian actors should, in the spirit of complementarity, collectively identify and address the pressures that threaten principled action in each operating context and identify appropriate negotiation strategies and escalation pathways. UN agencies and INGOs should use their leverage to support national and local partners in pushing back against demands from authorities that erode principled and effective response. More broadly, the system must create conditions that enable principled action for all actors – through balanced risk and counter-terrorism compliance, inclusive decision-making, and equitable funding, as well as by assessing performance against outcomes, such as impartial coverage and community perceptions.

Funding systems are one of the strongest determinants of behaviour. Current mechanisms often reward competition, short-term delivery, and institutional visibility. The UN competes for funding, while managing high running costs and staffing parameters governed by member states. NGOs, in general, largely depend on winning competitive calls for proposals for earmarked projects, with success based on showcasing technical expertise, programme quality, cost efficiency, and risk management policies, limiting their ability to support locally led initiatives or provide community-prioritised support. INGOs’ organisational budgets often depend on maintaining sufficient operational footprints to meet expected percentages of indirect cost recovery, driving a presence or operational footprint larger than it may need to be.

The most challenged – and excluded – by the humanitarian financing system are L/NNGOs, who have limited access to national and international sources of financing. Despite Grand Bargain efforts, L/NNGOs still typically receive just 3% and 4% of direct financing, with RLOs for example receiving an estimated 0.1% of global funding. They depend heavily on earmarked grant funding for their humanitarian work, marked by high compliance obligations and limited core cost coverage. To be competitive, L/NNGOs are often forced to under-cost budgets and overpromise to “win” or remain eligible for sub-grants.

Like INGOs, L/NNGOs’ funding is also primarily short-term project funding. Their institutional strengthening is often overlooked – including by more development-focused donors. They are left struggling with funding gaps, along with an inability to meet core costs, attract and retain skilled staff, or build reserves.

Flexible funding does not imply an absence of accountability, but the necessary freedom to adapt funding to respond to community-driven needs and fund locally led and developed programming. Keeping to the spirit of a “Bargain”, the provision of flexible funding would also imply international and national NGOs committing to:

Local organisations often face the highest levels of operational, political, legal, and security risk. Yet they frequently receive the least protection, support, or risk mitigation. Partnerships are largely shaped on the basis of the funding partners’ interests and risk dynamics, as per ISO 31000 risk standards.

Compliance and liability are contractually shifted “downstream,” while strategic influence and political cover remain “upstream.” This imbalance undermines trust, discourages principled action, and places a disproportionate burden on local responders.

L/NNGOs report a lack of meaningful dialogue and support in risk identification and mitigation. Due diligence and other capacity assessments are often built from the perspective of the funding partners’ risks, not that of the operational actor. Shared risk management often necessitates high degrees of trust, flexibility, and dialogue in both prevention and reaction, not easily achieved under short-term funding arrangements and in highly complex operating environments.

Likewise, the risk burdens cannot simply be shifted to the INGOs. Without the benefit of international organisation privileges and immunities, INGOs navigate regulatory challenges domestically and internationally, including registration requirements, counterterrorism, sanctions and banking regulations. In addition, as grant signatories, they often are left with the full liability for losses or compliance breaches of themselves and their partners, even if non-negligent. This full liability burden shapes partnership dynamics, including contracting conditions, budget allocations, and operational constraints.

Strategic and operational decisions, including response design, partner selection, technical standard setting, access negotiations, resource allocation, and enabling services are still predominantly made by – and designed for – international actors. Larger national organisations may participate in coordination mechanisms, but often with limited influence over the agenda or final decisions. Smaller, local, or specialised actors are expected to adapt to systems that were not built with their realities in mind. In some contexts, international coordination mechanisms duplicate or overshadow existing local structures. Affected communities are consulted but rarely drive the definition of priorities or the identification of the best-placed actor. The challenge remains around how those resourced and mandated to lead coordination can be better informed by the requirements of those delivering – the ‘end users’ of the system – so these services do not primarily serve the coordination architecture itself.

Trying to reach people, with less resources and in the most challenging environments, means coordination and support functions must be contextualised and support operations, particularly in technical areas that are often highly specialised. However, rather than being sustained or localised, in some cases these functions are being stripped from the system.

Delivering assistance, managing risk, and keeping staff safe will require working together towards a shared understanding of what the critical functions are and how these will be delivered through new complementary approaches. Reforms to coordination must ensure lighter, locally led structures that are intentionally reinforced by international capacity where needed, strengthening accountability to affected people and upholding quality.

Despite years of commitments, most responses still lack a deliberate pathway to shift leadership, resources, and accountability to domestic actors. Recent localisation baselines, including in Iraq, show persistent gaps in funding, leadership, and policy influence for local actors, even in long-running crises.

Humanitarian actors cannot all become development actors, but humanitarian actors must adopt a double bottom line: (1) Saving lives and protecting people (2) Maximising local capacities and resources for long-term recovery. This embodies the nexus approach and recognises humanitarian aid cannot resolve protracted crises or systemic injustice.

Responses must be time-bound and planned, with a clear transition strategy to local actors and authorities as soon as conditions allow. Humanitarian response must return to being the exception rather than a protracted solution and there must be true complementarity between humanitarian and development funding.

Humanitarian complementarity will not emerge organically – it requires a deliberate redesign of how the system is funded, led, coordinated, and mutually held accountable. Each actor has a distinct and essential role to play and must be supported to contribute where they are genuinely best placed. The goal is a system that is more equitable, efficient, and ultimately more effective in serving crisis-affected communities.

Rather than defaulting to direct delivery, international actors need to serve as conveners, brokers, and technical supporters behind locally led responses, providing technical and surge support, helping connect local responders to funding, and facilitating advocacy for crisis-affected people and local partners’ priorities internationally. Humanitarian donors need to reform funding mechanisms to enable this paradigm shift.

In addition to jointly continuing to work out how we best collectively navigate in the fast-changing humanitarian dynamics, including harnessing new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, forging increased links among development, climate, peace, and health sectors, the following recommendations outline a few first steps that donors, UN agencies, international NGOs, local and national actors, can take to help enable a complementary, people-centred approach.

To further forge their leadership role in humanitarian response mechanisms, L/NNGOs are encouraged to:

Beyond current reform efforts, including UN80, UN agencies are encouraged to:

In the spirit of “as international as necessary, as local as possible” INGOs are encouraged to:

Understanding and working within the range of their diversity, donors are encouraged to: